Tiago Rodrigues: “Theater is one of the few spaces where you can still tell the truth”

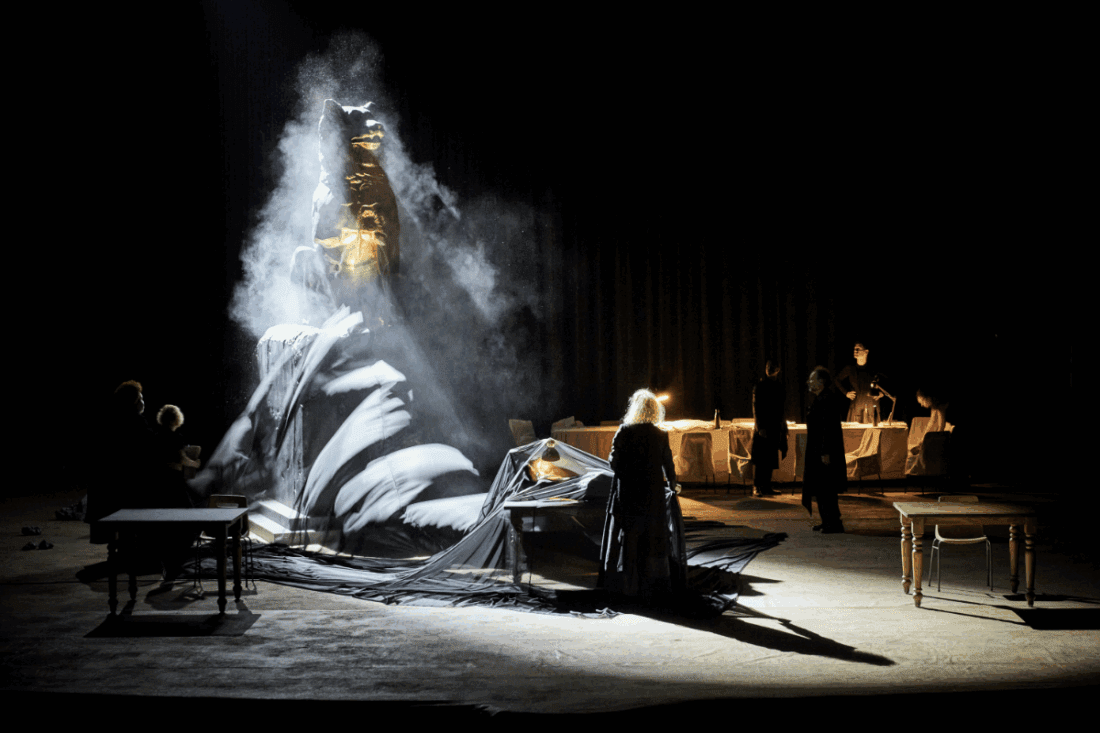

In his first alliance with the Comédie-Française, Tiago Rodrigues (Lisbon, 1977) does not resurrect Hecuba of Euripides, convene and challenge it. Into Hécube, Pas Hécubethe Trojan Queen – Vídua, slave, a torn mother – is reborn in an actress who gives a mother today: a woman who cries justice for abuse of her son with autism. The theater becomes an open field of pain. Rodrigues writes with the actors in the center, in an austere atmosphere where the word is resistance, time breaks and fiction strikes in the face of reality. From the helm of the Avignon Festival, the Portuguese director talks about a theater where emotion is insubornable and memory, political quite.

Tiago Rodrigues

Barcelona Theater: What brings you, as a creator, to work with a classic text? How do you transform your way of doing theater?

Tiago Rodrigues: It all starts with the tongue. He had already worked with classic authors in works that were not always reinterpreted. I wanted to explore that clear and powerful style, using words written twenty-five centuries ago. With Hecuba, Euripides It opens a crack in the classic tragedy: for the first time, it allows you to feel the inner life of the characters. Perhaps he was the first to conceive a psychological reading of the protagonists. It was revolutionary. And this revolution still resonates: Hecuba He talks about vulnerability, justice, revenge and institutional responsibility in the face of the most fragile.

Why, despite occupying a central place in Euripides’ tragedy, Hecuba is still a forgotten figure? Who really is this tragic queen?

The queen of Troy, enslaved after the fall of the city, sees her children turned into a war loot. When he discovers that the last, entrusted to the King of Thrace, has been killed and left without burial, orchestra his revenge and presents the case in Agamemnon. Wound but demanding justice, Hecuba is also a political symbol. This dimension, which has always fascinated me, culminates in a work that speaks of how society treats vulnerability. It is, first of all, a powerful material for thinking the theatrical representation and its public dimension.

Your tragedy, you have called Hécube, Pas Hécubestarts from a concrete social reality.

Yes, clearly. Into Hécube, Pas Hécubeviewers are witnessed by a mother’s intimate tragedy, Nadia, a son with autism of whom she was abused within the institution that had to protect her. The case, real, shocked Switzerland and followed him closely while working in Geneva. It made me think of how seemingly protected societies can be deeply negligent with the vulnerable. From this, I read testimonies, medical literature, articles … and all this was transformed into poetry and theater.

How do Nadia’s story and Hecuba myth converge or come into tension?

Nadia’s tragedy, like so many mothers who are fighting, resonates with that of Hecuba. When he uses his words, he denounces a crime that hits her personally, but is greater: the abuse of vulnerable children. As Hecuba in front of Agamemnon, Nadia faces a dehumanized institution. His pain is transformed into strength and denunciation. And when justice fails, as he says in the play, “opens the door to revenge.”

The analogy between Hecuba and Nadia alters temporary linearity and transforms the reception of tragedy. What role do the Flashbacks in this narrative construction?

Yes, the confusion is wanted. At first we see an actress as a mother. But little by little, Nadia lives Hecuba’s texts as part of her own reality. The stage words are filtered in his intimate life, and time becomes labyrinthine. This fusion gives it a tragic strength. Only Nadia is a fixed character; The rest of the actors jump from role in role, as if they reflected their destabilized gaze.

When Nadia’s gaze is blurred, the viewer also loses references. How do you use lighting and other resources to convey this sense of opacity and confusion?

We worked with a palette that mimics a dog’s vision: yellow and blue-violacios. Hera turned Hecuba into a bitch as a punishment, an image that symbolizes a fury that is not covered. It is the same fury of so many mothers who claim justice, such as those of the Plaza de Mayo. This junction between mourning and demand fascinates me. Theater can be an emotional and political assembly at the same time.

“When an actor plays a classic, he rewrites him”

How did the distribution of the Comédie-Française react to this proposal that mixes reality and fiction?

The show is a collective writing. I arrived at rehearsals with a dozen open pages. We read, talked about, imagined as children. From this game I built the text thinking about the scene. The result brings the company’s living imprint. When an actor plays a classic, he rewrines; Here, even more so: their lives have strained in the story. This porosity may have deeply affected them.

Do you think Greek tragedies still help us understand the present?

Hecuba He talks about justice, mourning and institutional violence, still urgent issues. The theater gives to the memory and the word a public, political function. As Heiner Müller said, “the theater is the place where we dialogue with the dead”, but also with the living. In a world where institutions fail, perhaps theater is one of the few places where you can still tell the truth. We will not change the world only with theater, but we will surely change it better with it than without.

More information, pictures and entries: