symbolic power, ESS and uncomfortable voices – Athenaeum

What happens when a seemingly harmless advertising campaign awakens painful collective memories and opens the door to uncomfortable debates about identity, privilege and inequality? The recent case of the American Eagle brand, which launched a campaign with the slogan “Sydney Sweeney Has Great Genes”, is a good example of how a phrase can carry a symbolic load capable of generating controversy, but also reflection.

This fact invites us to look inside our own ecosystem. At a time when the social and solidarity economy (ESS) is being claimed as a way of social and economic transformation, it is essential to ask ourselves how we manage imaginaries, symbols and narratives from within. What references move us? What stories do they represent us? And how do we address the tensions that arise when these stories come into conflict with the structures of privilege that, sometimes unwittingly, we perpetuate?

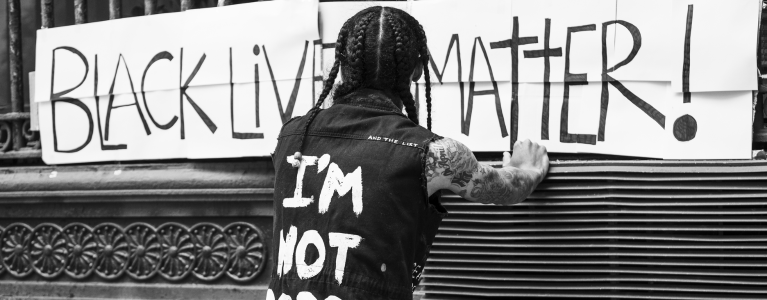

Within this framework, it is appropriate to put at the center an often avoided debate: how is cultural and racial power expressed within cooperativism? And how can it reproduce forms of domination if there is no critical review of practices, voices that have authority and forms of organization?

From the migration group of the Xarxa d’Ateneus Cooperatius (XAC), it has been working for some time to open participation spaces where migrated and racialized people can have an impact not only as beneficiaries, but as protagonists. These are experiences that not only provide alternative knowledge, but that actively question the hegemonic frameworks and propose new ways of organizing and relating within the ESS.

These projects confront us with an uncomfortable truth: good intentions do not guarantee real change. Because it is not enough to add diversity to discourses, it is necessary to review the decision-making mechanisms, the legitimacy criteria and real access to resources and power spaces.

It is in this context that “discomfort” becomes a powerful tool. Recognizing it, listening to it and supporting it can be the beginning of a transformative process. It is not about blaming, but about assuming collective responsibilities and building more equitable relationships within the ESS spaces themselves.

Relating a media case to the cooperative world may seem like a risky exercise, but it is also necessary. It reminds us that communication is not neutral, that every word carries a weight, and that the narratives we construct can be spaces of liberation or reproduction of inequalities.

Opening spaces for critical dialogue about how we communicate, who occupies the stands and from where they speak, is not only important: it is essential if we want an economy that is truly centered on life and not on privilege.

Albert Rodríguez Hilario