Ariadna Gil: “An unfaithful woman is still seen differently than an unfaithful man”

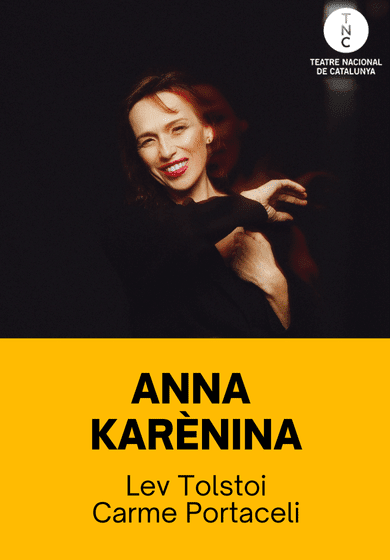

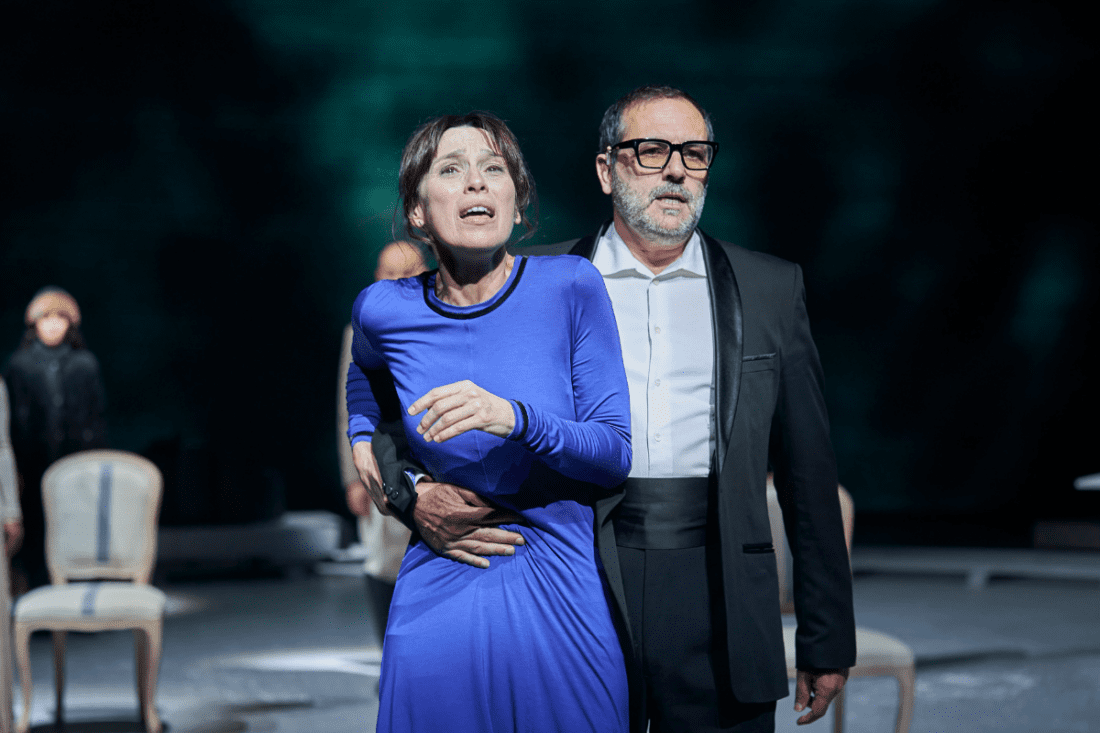

“All happy families look alike; each disparate family is disparate in its own way.” At this crossroads of thought Leo Tolstoy (1828-1910) begins Anna Kareninahis most famous novel, an important enigma that, since it was published in 1877, is also of our time, because it nurtures and makes all doubts grow, because it questions what life is worth living. On one side, we have the strength of temperate conjugal love, the tedium of an orderly life without allurements; on the other, the tempting call of unfettered freedom, of desire and passion that make us feel alive as never before, but also increasingly fragile, even to the point of self-destruction. Carme Portaceli takes the lead in this stage adaptation of Leo Tolstoy’s novel and places Anna Karenina on stage to be judged, but it gives her a chance to explain what really happened and what she heard. Ariadne Gil heads the cast of a production that, in order to reinforce the validity of the classic in today’s era, opts for a simple staging, without period costumes or elements that refer to the end of the 19th century. The train tracks, which give the beginning and end to the story, form the main scenography of the show.

Teatre Barcelona: You already did it with Carme Portaceli Jane Eyreby Charlotte Brontë, in 2017 at Teatre Lliure, and now you repeat experience with Anna Kareninaby Leo Tolstoy. Two great characters.

Ariadne Gil: True, rarely does one have the opportunity to do something that changes you deeply. Jane Eyre and Anna Karenina are two very different characters, with very different intensities, but they have moved me in an extraordinary way and will always accompany me.

What does it mean to do today? Anna Karenina?

The issues today are the same as they were a hundred and fifty years ago. The search for happiness, trying to understand our existence and realizing that things haven’t changed in many ways. I mean the social gaze, which continues to be different about a man or a woman who have done the same thing. It is very difficult to summarize what Tolstoy does in this novel, because he talks about so many things that it is very difficult, but I think that the theme that hovers throughout the story is the meaning of life and the search for happiness, specifically with a very important presence of love in this search for what makes us happy, to give meaning to our existence. And it seems to me that it is a subject that passes the years, the centuries pass and that the human being one day questions it, very soon, especially, when he becomes aware of the absurdity, of human existence, of death, of so many things that make you wonder why we are here, where we are, and it seems to me that this remains unanswered. We have looked for them in so many ways, but we keep asking ourselves questions.

“The two people I love in this world are my son and Vronskij.” Both are incompatible. There is no solution, or maybe there is: death.

In the case of Anna’s character, she is faced with a brutal dilemma, either she lives and loves or she continues to live a life that does not satisfy her in any way despite being close to her son. It’s a tragedy. I choose to stay with my son or live my story, my passion, my love story, my search for this happiness. That’s one of the things that causes me to go into this spiral of somehow not being able to live in peace.

“The characters are of beastly richness and complexity”

Anna tells Vronskij again and again: they have nothing to be ashamed of, because their love is true and therefore legitimate. For her, would the humiliation have been to remain in the marriage, in order to keep up appearances?

I think Tolstoy also talks a lot about how much we follow our own will, or there is a destiny that leads us or we don’t have to follow this kind of destiny that presents itself, how much we are the ones who choose and make the decisions or are the things that happen to us and then we think about them. I think in this case it’s a character that, like us, sometimes we act impulsively without knowing why and then we find the reason or try to justify why we did what we did, why we followed according to what instinct, according to which thing, and then we think that we didn’t decide it, to what extent you decided it, it was an act that was impossible to stop or that you didn’t want to stop. All of this also flies in the story and in these characters who are of beastly richness and complexity.

Anna is a victim of those eyes that judge her with a rod different from those with which they judge Vronskij, because being a woman, she had the pretension to be free, to decide who to love.

Yes, it is very present in what society was at that time, Russian society at that time, the possibility of divorce or not and how, child custody, all of this is also discussed a lot in the novel and it is something that also crosses the centuries; an unfaithful woman continues to be seen differently than an unfaithful man, judging differently the behavior of a woman who is with many men or a man who is with many women, we don’t know why this continues.

Wishing to live in freedom comes at a cost.

The isolation the character finds himself in is one of the scariest things that can happen to a person. Remaining isolated because she has deposited everything in love and what she lives. And if that doesn’t work, that doesn’t go well, the fact of being alone, of being isolated, that everything is that person’s life and not theirs, this creates an imbalance, a depression deep down, tremendous, because there is nothing worse than being alone.

Tolstoy never judged Anna Karenina.

Unlike us, who constantly judge what others do, how they are, why they did this… On the other hand, Tolstoy does not judge anyone, there are no good and bad, he challenges us in a very direct way.

What goes on inside you while playing Anna Karenina?

It is a set of very strong things, all of them, and they are changing. In other words, you also build the essay process little by little, you have a lot of information, because the novel gives you a lot of information about what he thinks, what he feels, what he is like, how others see you, all the main characters, which we’ve been building in a way and finally we do a version, we do an interpretation. It is impossible to explain the novel, the novel is a masterpiece and I think that here is Carme Portaceli’s version and how she wants to tell this story that touches her in a special way.

Carme Portaceli likes to think about theater with all its social and political implications. What dimension does this adaptation adopt in the Great Hall of the TNC?

It’s a very stripped down version. Well, it’s the seven main characters that tell the story and then there’s one character that’s kind of hovering over and accompanying those characters. A very particular look between Tolstoy and the consciousness of the characters that allows us to interact with ourselves as well. Then it’s a feature that we’ve also made a lot towards the public, that is to say, I think it’s basically a story that seeks to understand ourselves and not inwards, but by asking us questions. The novel asks you a lot of questions, or rather provokes a lot of questions. And I think this is how we defend it, asking ourselves questions and also asking the viewer why what happens to us happens to us.

It seems that the theater has been your priority in recent years. Maybe now it presents you with more challenges than cinema? Doing plays by Shakespeare, Chekhov, a monologue by Marguerite Duras, Tolstoy…

yes, [riu] great challenges, no doubt. Far more beastly and far more interesting challenges, really, yes.

More information, images and tickets at: